As angels, we want to believe in the adage that “our human capital helps to de-risk our financial capital.” But what does that mean, and is there any factual basis for our faith? At Launchpad we wanted to find out, and we looked to see if we could use our data to do it.

We knew intuitively from experience that the more we were involved with a company, the better the outcome tended to be. By involved we referred mainly to having done a fully diligenced project to really get to know the company, leading their seed round of financing where possible (i.e. defining the termsheet, the capital staging strategy, the post money) and establishing the approach to proper governance.

To see what our data told us, we looked at 105 portfolio companies that had been with us for at least 18 months from our initial investment, including both active companies and exited portfolio companies. As expected, we did see a lift in returns associated with both doing full diligence and with leading the round and providing the termsheet.

As discussed in a previous Data Insight from March 2021, with full diligence we saw a lift in returns of 54% over the deals where we did not do full diligence.1 When we looked at companies where we had led the round and provided a termsheet, we saw an even greater lift in returns of 162%.2 This eye-popping increase makes sense because, while we strongly prefer to lead rounds, we know we cannot always do it, and are quite selective about when it makes sense. We tend to only do it where we feel we can anchor the round with enough support to be a good lead.

That was interesting data, but did not really address our central question. Diligence and leading rounds are not exactly what is meant by angel “human capital.” They could more properly be classified as deal-making skills. So what about real human capital? Actual helping and advising? Did we have any data that could shed a more direct light on our “helping hands” hypothesis? Well, it turns out we did.

The pathway we found was to focus on board service. Board service is not the only way angels add human capital to a startup, but it is one of the more consistent and important ways. As we’ve pointed out before, a good start-up board director can add tremendous value: in addition to providing the steady and watchful hand of basic governance, a good director can give advice, coach a mentor a CEO to reach his/her full potential as a leader, make introductions to prospective customers, partners, help with organizational development and hiring, and keep the focus on identifying and executing a good exit strategy.

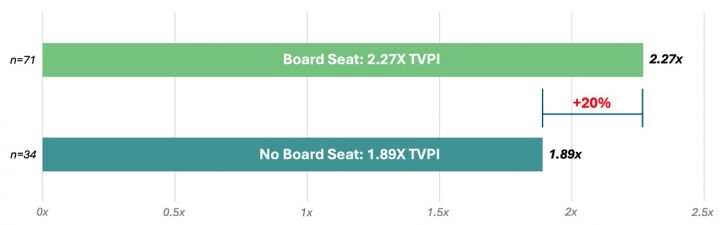

Not only was board service a critical conduit for human capital, we had some data we could analyze. It turned out that within that same 105 companies aged 18 months or more from first investment, we had 71 where we took a board seat and 34 where we didn’t. In the companies where we took a board seat, we ended up with an average TVPI or total value to paid capital of 2.27X. This compares to an average TVPI of 1.89X for the companies where we did not have a board seat. That is a lift of 20% associated with having some experienced human capital directly engaged in working with the company in a systematic way.

[1] 67 companies with full diligence returned an average of 2.47X in Total Value to Paid In Capital (includes both realized and unrealized returns) compared to the 38 companies where we relied primarily on 3rd party due diligence, which returned an average of 1.6X TVPI.

[2] 34 companies where we provided the termsheet returned an average of 3.34X in Total Value to Paid In Capital (includes both realized and unrealized returns) compared to the 71 companies where we relied primarily on company led rounds or 3rd party termsheets, which returned an average of 1.27X TVPI.

Because we typically take a board seat when we lead a round, and we typically lead a round when we do full due diligence, there is undoubtedly some overlap in the outcome performance drivers, but the overlap is not all-encompassing – we take board seats far more often than we lead rounds (and about as often as we do full diligence).3 The 20% uplift we could isolate as being attributable primarily to having a board seat was a significant improvement in outcomes. Naturally, we wanted to leverage it, and so we set out to develop a programmatic way to do it.

Step One: Maximizing the Number of Board Seats

The first step was obviously trying to obtain board seats as often as possible (and pushing for at least an observer seat where a full board seat was not an option). Success here was not just a function of leading rounds where possible. Equally important was teaching entrepreneurs why they should not fear boards and to understand the value that great directors can bring. (And, conversely, avoiding deals with entrepreneurs who could not get that through their heads). Success also meant being more thoughtful and selective about which rounds we chose to back. If we were going to be a tiny player in a round, not have a board seat, not have any say in the current or future deal terms, and not have any sway in discussions around capital staging, did we really want that company in our portfolio?

3 What is reflected in the numbers is that we are much less selective about taking board seats and doing full diligence (71 companies in each case) than we are about leading rounds or investing without full diligence (34 companies in each case) – we always want to do diligence and we always want to take a board seat. We often get board seats even if we are not leading the round simply by virtue of the fact that we are putting one of the more significant amounts of money into the round.

Step Two: Maximizing the Value of Each Board Seat

- First, it meant training our directors to be as effective as they could be both in terms of basic knowledge and more advanced skills.

- Second, it required being proactive and having the conviction to swap directors out when the fit and effectiveness was sub-optimal or the chemistry with the CEO wasn’t working.

- Third, it meant creating an environment where our directors could support each other and learn from each other. Our main mechanism for doing that is a standing quarterly meeting of all of our board delegates where we discuss on-going portfolio company issues and crises, receive continuing education about legal, economic, industry and regulatory developments, and review case studies, discuss lessons learned and conduct post-mortems.

- And the fourth element was keeping our board delegates focused on exits. Experience has taught us that good exits don’t just happen by accident, they are deliberately created with continual work over time. As a result, we educate our directors on the importance of driving good exits, and we track (by survey) and regularly discuss each portfolio company’s progress toward exit.